Käthe Kollwitz

CURRICULUM

Käthe Kollwitz: Art and its Contexts

By Andrew Vlcek

Discussion and Research Questions

Resources

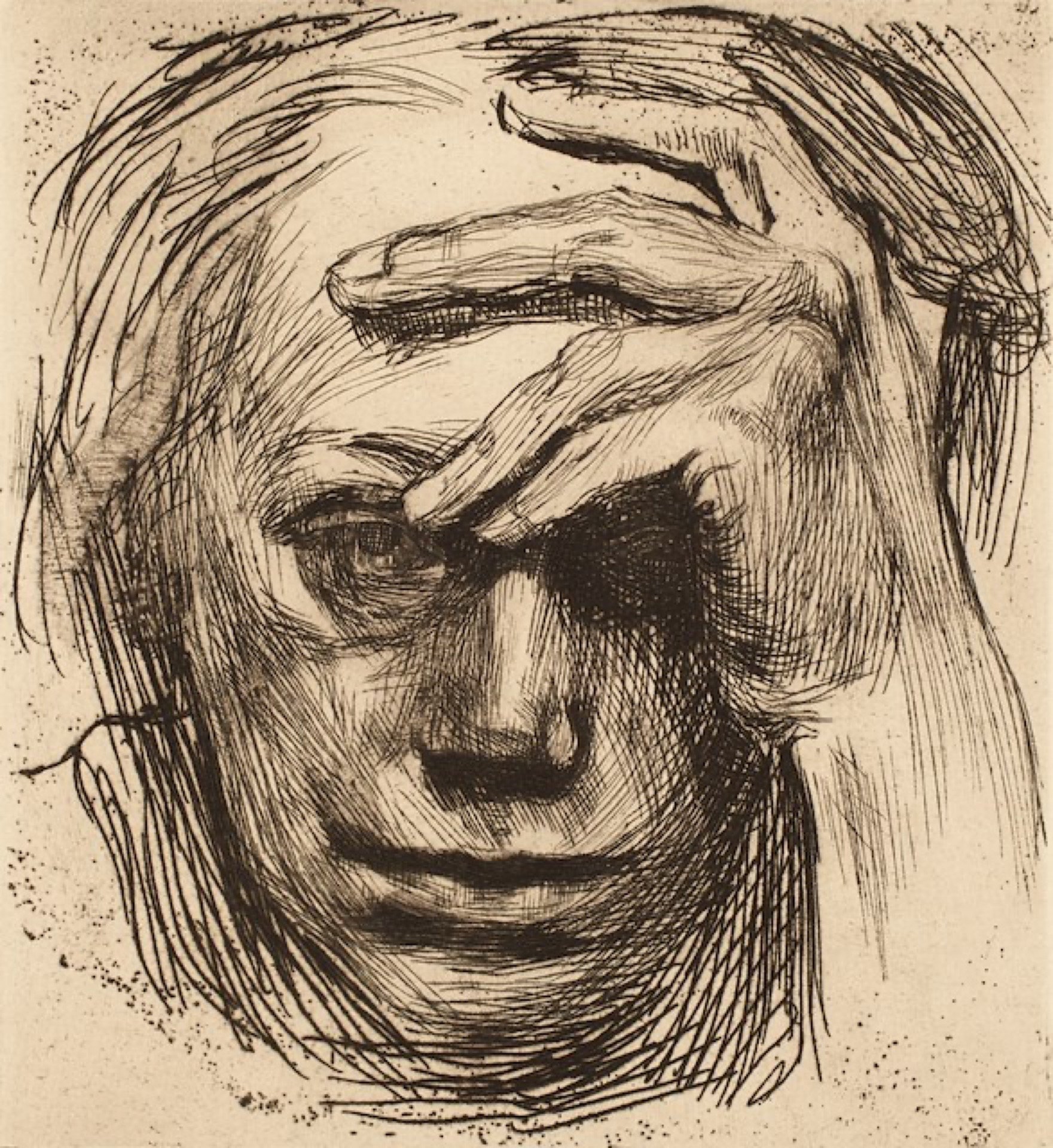

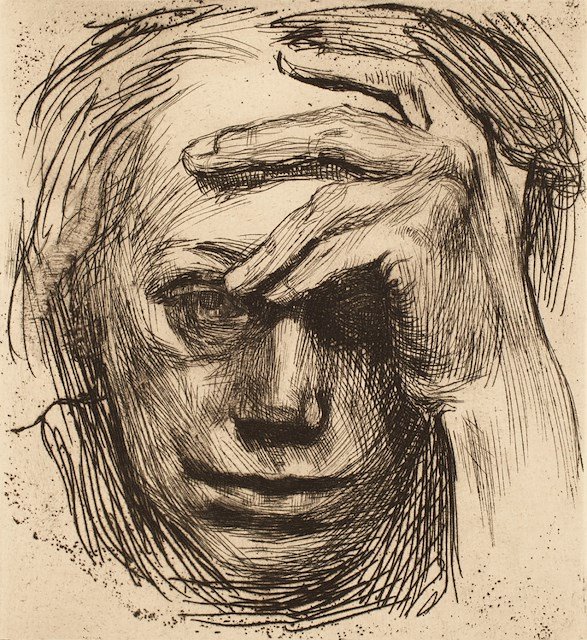

When we turn to Käthe Kollwitz’s most famous works, they present us with a classic case of the question of the “use” of artworks for non-artistic purposes in which we see a dramatization in images of burning political and social questions of the day. What is the line in works like these between “art” and “propaganda”? Can we gain any perspective on this issue from Kollwitz’s more superficially “non-political” works, such as the self-portrait in the Permanent Collection?

Artworks confront the viewer both as the vehicle or occasion for an immediate aesthetic experience, but also as “mediated” carriers of historical, material and personal connections. Particularly in the modern era, in which mass democratic politics accompanies the mass dissemination of images, the mediated use of artworks for political or other purposes has become extremely significant. Since the early modern era, this has occurred on the side of the artist, in which the artist’s private political convictions or the agenda of an institution or organization stand out perhaps more strongly than the religious background or private patronage of recent past centuries. Yet it has also occurred on the side of the public, which has increasingly been trained in the “hermeneutics of suspicion” (to discern hidden agendas in cultural objects) and by which works can sometimes be reduced to nothing but carriers for someone else’s beliefs, agenda, or identity.

Moreover, with the rise and mainstreaming of “difficult” abstract or conceptual works, the artists’ overt statements of purpose and curators’ and critics’ post facto written articulations of the nature or meaning of artworks now seem to accompany these works as integral elements, at least from the point of view of the museum-goer or casual reader of texts on art. In such circumstances, an artwork becomes not only a carrier for beliefs or identities but is actually incomplete without them, leaning on non-aesthetic external elements to complete its aesthetic task.

20th century political poster art provides a striking illustration of some of these relationships. Artists of undisputed greatness, no mere hacks for parties or governments, deployed their talents consciously and deliberately in the arena of mass media politics, creating works that maintain their visual resonance and power even when the occasions for their creation have passed out of living memory. The works of Kollwitz provide a particularly useful example here.

Kollwitz was a second-generation adherent of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) and later a non-party sympathizer with Communism. Though she never joined either party, her work was closely associated with the radical wing of German socialism in the period before Hitler’s accession to power. A casual look at these associations might label her work, then, as “propaganda,” whatever her talents or the aesthetic impact of her works. Our tendency today, perhaps, would be either to reject her work out of disagreement with these political positions, or to approve it for the same reasons, depending on our own convictions.

On the other hand, a viewer might imagine himself transported to a distant future time in which the political conflicts of Germany and the larger world before 1945 are as temporally remote as the pyramids and as unlikely to excite present passions as the dynastic struggles or external wars of the Egyptian pharaohs. How might the works of Kollwitz strike us from such a point of view? Could experimenting with such a perspective allow us to grasp a universal significance within a work of art that goes beyond its contemporary context?

In Book III of his The World as Will and Representation, Arthur Schopenhauer offers the following reflections on paintings with historical or Biblical subject matter, which might be relevant to our hypothetical far-future anthropologist:

The historical and outwardly significant subjects of painting have often the disadvantage that just what is significant in them cannot be presented to perception, but must be arrived at by thought. In this respect the nominal significance of the picture must be distinguished from its real significance. The former is the outward significance, which, however, can only be reached as a conception; the latter is that side of the Idea of man which is made visible to the onlooker in the picture. For example, Moses found by the Egyptian princess is the nominal significance of a painting; it represents a moment of the greatest importance in history; the real significance, on the other hand, that which is really given to the onlooker, is a foundling child rescued from its floating cradle by a great lady, an incident which may have happened more than once. The costume alone can here indicate the particular historical case to the learned; but the costume is only of importance to the nominal significance, and is a matter of indifference to the real significance; for the latter knows only the human being as such, not the arbitrary forms.

Here, Schopenhauer suggests a dual relationship in artworks between what we might call “internal” and “external” meaning. As he explains elsewhere in this text, the work itself gives a timeless instance that sheds light on essential human qualities. In fact, if it clothes this instance too heavily in materials that only “the learned” will recognize, it may fail at expressing these essential qualities; a work’s internal meaning may be swamped by its external meanings. We will move from the realm of perception into the arena of thought, as when we attempt today to analyze an artwork solely in terms of its contexts.

To be sure, Schopenhauer’s position depends upon a contentious view of the ideal aesthetic experience as fundamentally one of what he calls “contemplation,” in which the beholder of an artwork exits from the confines of the world of causality into a kind of higher or purer perception of the timeless ideas conveyed by art. Yet, leaving aside the debate on these matters, we can ask the question: is an artwork ultimately “reducible” to its personal, social, or historical contexts, even when these are only accessible to “the learned”? What would be left of an artwork if all it is is the contexts with which it is involved?

In Kollwitz’s famous “In Memoriam Karl Liebknecht,” the murdered German Communist leader’s funeral requires specialized historical knowledge to “understand” in its external (or as Schopenhauer says, “nominal”) significance. One would need, first of all, to know the identity of Liebknecht; one would need to recognize the figure in the background to the left, identified as Russian Communist leader Vladimir Lenin. Our hypothetical future student would need, perhaps, to know some “archaeology” in order to recognize the typical workman’s jackets and caps worn by the mourners. Amid all this, one might wonder whether the print can still have any “real significance” to the viewer ignorant or indifferent to these contextual images and allusions. However, is there some remaining force in the picture that simply goes beyond its reduction to these elements?

The latter question raises important interdisciplinary questions, especially for the student of politics and history. After all, even if we primarily wish to enter the context of a work as archaeologists and understand what it meant in its time and to its original audience, we are inquiring about how the work, as a work, struck them. This invariably raises questions of the the work’s composition, execution, and formal qualities and how these impacted the original viewers and their sensibilities. Today, when works in the tradition of Kollwitz’s prints overwhelm us with an obvious political agenda, we call such works “heavy-handed” or “didactic” and understand them as making a cognitive appeal to our beliefs, hopes, fears, or prejudices. At the same time, we also may be bewildered at the attempts by critics or curators to connect cognitively a work of disembodied abstraction to concrete concerns – does this image really have to do, in itself, with the stated issue of the day?

Formal analysis can help here. Kollwitz, for example, combines recognizable subject matter with the techniques of expressionism, and the availability of these novel methods to her as an artist was as much a part of her “context” as the more immediate political issues of war or poverty depicted in her works. For the German of 1919 standing before her works, the formal quality of her prints may very well have been as striking or as novel as the depicted scenes were excitations of political and social passions. Again taking on the role of an antiquarian art enthusiast of the distant future, we might say that even if nothing else about Kollwitz’s works’ social and political contexts still interests or excites us, we may nevertheless feel ourselves engaged by these formal qualities. Further, by reaching out to the way in which this specific image, depicted in this particular mode, impacted its audience, we may be able to understand them in a richer way than merely approving or disapproving the “message” of the work and its audience’s presumed reception of it. In this way, the same historical or political gaze that felt itself unable to see artistically can, by achieving this kind of “formal” seeing, better understand its own interests.

Returning to Schopenhauer’s division between “nominal significance” and “real significance,” we can compare this to the distinction between “form” and “content” in artworks. “In Memoriam Karl Liebknecht” gives to our perception the scene of a public mourning for a dead person. Assuming the absence of any information on the part of the viewer about the “nominal” contents of this scene, we can only lean upon the artist’s modes of expression (the work’s form) to deliver the “real” contents to perception with the power necessary to move us.

This form versus content distinction is not exactly the same as Schopenhauer’s distinction between real and nominal significance. But consider that, if we eliminate from consideration the nominal significance of the work, or much less “external” matters of the artist’s opinions or identity, then how might we distinguish between various works with the same or similar subject matter as we attempt to discern them in their real significance the one from the other? If we take on this experimental point of view that omits historical or other context, then we have works that “look the same” in terms of their depicted objects. In this situation, the only way to discern between them — or better, the way in which they would present their differences to us — would be their formal qualities, their natures as pictures.

What happens when we add to this formal power concrete knowledge of the work’s nominal content? This presents the possibility of an interdisciplinary synthesis of Schopenhauer’s “nominal” and “real” significance, something like a “total significance” in which the artwork becomes itself through both its modes of significance, mediated by the power of its form.

Naturally, we can also reach externally into an artist’s larger oeuvre for insight into these formal characteristics. The permanent collection’s work, for example, allows us to discern the same haunting and troubling line work in Kollwitz’s prints, even across works that differ fairly greatly in their composition and technique. A nearly intangible element – the voice or feeling of her line – emerges then and gives us a grip on that which makes these works such successful carriers of a real, internal significance.

So here also for the student of politics and history the artist appears in her own right as an object of inquiry, beyond the conscious intentions she attempted to enact in her art (political, artistic, or otherwise), and in the fullness of her self-contained human worldview.

Questions for Discussion

Compare the permanent collection’s print to some of Kollwitz’s other well-known images. What differences in technique are apparent to you between this earlier work (1910) and her later prints from during and after World War I?

Consider Schopenhauer’s distinction between the “nominal” and “real” significance in works of art. Do you agree with this distinction? To what extent does it apply to works of abstract art that have no obvious nominal subject?

Cite some examples of political propaganda with which you’re familiar. Do Kollwitz’s “political” works resemble these? If not, why not?

Much of the idea of citizenship in a democracy involves an individual making a thoughtful and deliberative consideration of issues or problems, and then voting or participating on the basis of these considerations. Does this conflict with the emotional experiences involved in the appreciation of art?

Resources

Schopenhauer, Arthur. The World as Will and Representation. Translated by Richard Burdon Haldane and J. Kemp, 2nd ed., 1844. Translated edition, 1909.

MoMA Artist's Page for Kollwitz

Nazi and East German Propaganda Archive

Soviet propaganda posters (commercial site with large archive of images)