Japanese Prints: Yūgen

CURRICULUM

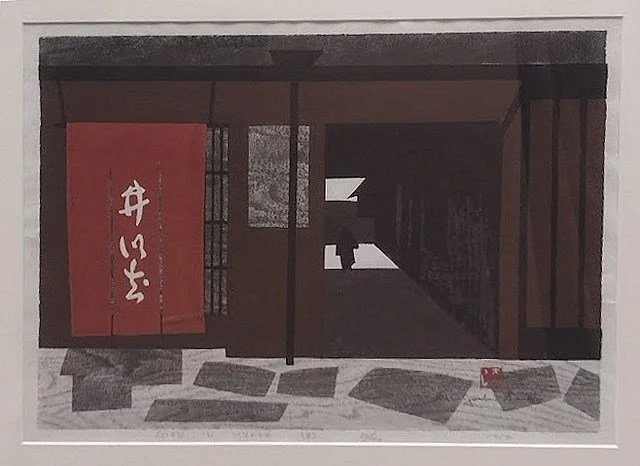

Kiyoshi Saito, Gion in Kyoto, 1959

Kiyoshi Saito, Obakusan, Nara, 1971

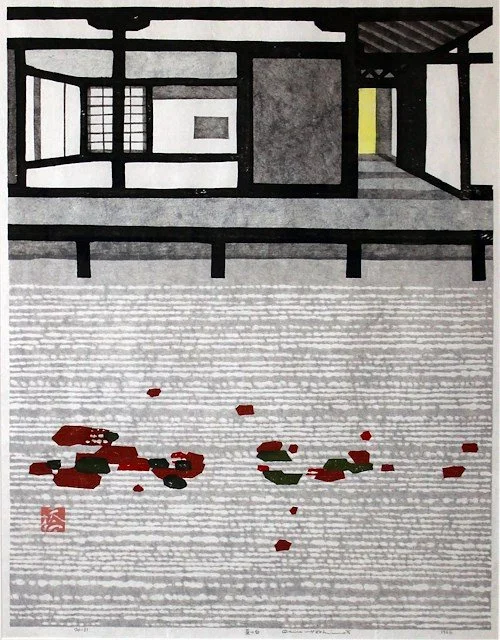

"Summer White" Natsu no Shiroi, 1966

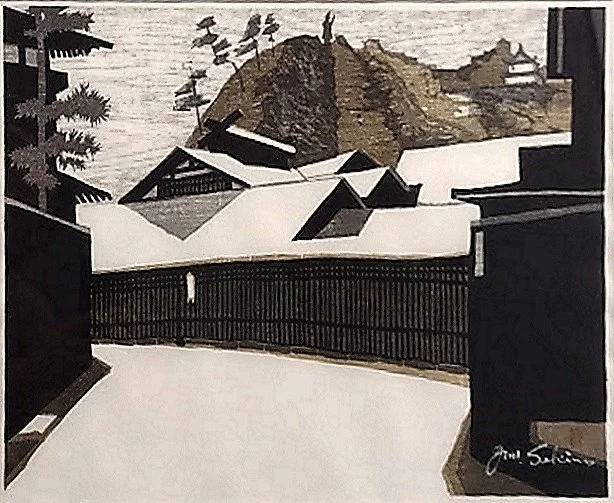

Junichiro Sekino, Village Snowscape, 1970

Junichiro Sekino, Haus: Temple Grounds, 1950

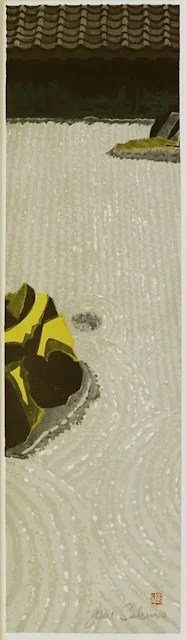

Untitled Temple Garden, 1950

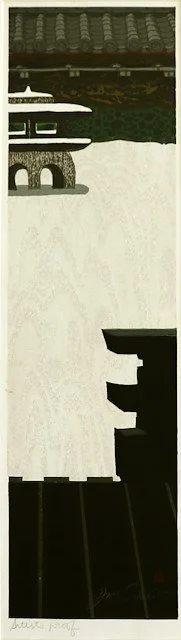

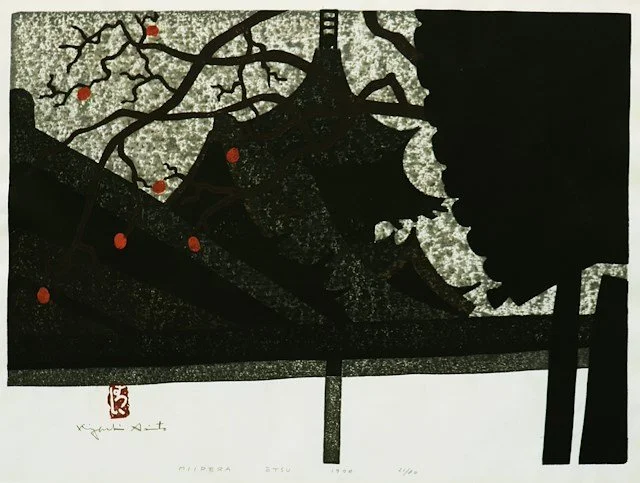

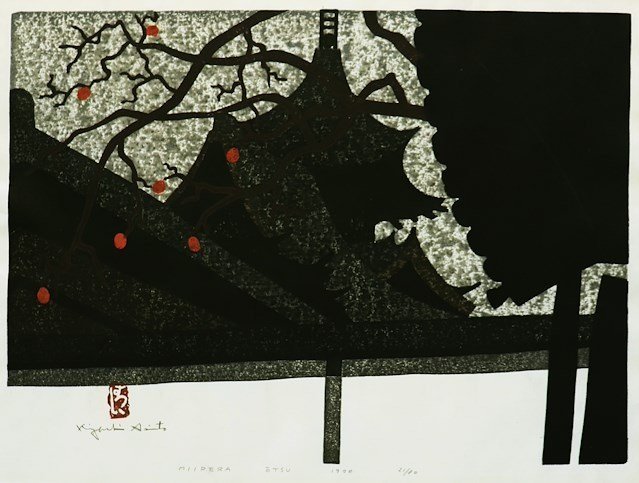

Miidera Otsu, 1970

Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645), Shrike in a barren tree (枯木鳴鵙図, Koboku meigeki-zu).

Essay: ‘Yūgen’ (幽玄)

By Benjamin Hoffman

‘Yūgen’ (幽玄) signifies unseen depth, shadow, and mystery. It is a tone or an atmosphere—as much a quality of a landscape as the mood of an observer. Yūgen is a sense of the invisible, or the infinite. But as an aesthetic quality and not merely an idea, as ‘the infinite’ may be, yūgen has to do with the limits of experience. It is evoked by the boundaries at which the sensible becomes insensible, or the visible becomes invisible—is obscured or vanishes into a distance or darkness. Dark night is perhaps the ideal type of yūgen, but complete darkness is merely unseen, strictly ‘ideal.’ So images of yūgen include: a dim figure framed by darkness; a fog-shrouded landscape; a disappearing path. Yūgen as a play of the seen and the unseen, as the ‘seeing’ of the unseen, gestures at what can never be seen. D.T. Suzuki notes that it has been called the appearance of the ‘eternal’ in the transitory, displaying the “secrets of Reality.” Zen master Dōgen's (1200–1253) zazen or seated meditation has been described as a practice revealing yūgen, by shikan (史官), or ‘calm contemplation.’ Steve Odin uses the philosophical language of phenomenology to present yūgen as a matter of both perception and the perceived: a feature of on one hand the ‘penumbra’ or the horizon (limits) of perception itself, and on the other hand the edges of a perceived figure against its background. As a mood, it concerns how we see as well as what we see; as a feature of a perceptual ‘horizon’ it reveals the limits of both seeing and the seen.

“When notes fall sweetly and flutter delicately to the ear,” … “A white bird with a flower in its beak.” “To watch the sun sink behind a flower-clad hill, to wander on and on in a huge forest with no thought of return, to stand upon the shore and gaze after a boat that goes hid by far-off islands, to ponder on the journey of wild-geese seen and lost among the clouds” (Zeami quoted in Waley 22).

Hisamatsu Sen’ichi writes: “The compound yūgen 幽玄 (lit. depth and mystery) is made of two Chinese characters: yū means ‘faint, dim’ and also ‘deep’; gen indicates the black color, the color of heaven, something far away, something quiet, and an occult principle” (355-356). The term emerges from Chinese Buddhism, in which it refers broadly to that which is beyond ordinary perception or the grasp of intellect. It passes into Japanese literary criticism, where it is used especially to describe waka poetry and in relation to ‘overtones of feeling’ (yojō). Yūgen is later associated with Zeami’s (1363-1441) nō theater, with its masked actors, extended silences, and slow movements. From its use in discussions of literature and theater the scope of yūgen as a descriptor is extended to visual arts, such as sumi-e ink painting. It is associated with shadows, dim backgrounds, and negative space—where for instance a figure invites attention to the emptiness or darkness that surrounds and contains it.

Yūgen is therefore a rather general term, in that it can be a quality of writing, acting, painting, and nature. In this regard it is like the words ‘beautiful,’ and ‘sublime.’ General as ‘broadly applicable’ does not here mean abstract. Yūgen like beauty and sublimity, as an aesthetic quality, is perceived. As a quality of experience, it is concrete. A comparison to the sublime is further invited by the notion that yūgen gives an intimation of infinity. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), for instance, identifies as a feature of the sublime its reference to the idea of infinity: the very large gestures at what is infinitely large; the very powerful, at what is infinitely powerful. The sublime therefore for Kant refers to boundless being—to God. Yūgen involves a quite different notion of the infinite: as not infinite being, but more strictly the ‘non-finite,’ or that which is beyond finite ‘objects’ of sense or knowledge: the extended darkness of a cosmos that cannot be finally or completely known. It involves a notion of the ‘infinite’ as, even, non-being, but a non-being or nothingness that is the beginning and end of phenomena, both womb and death.

The trace of the infinite involved in the sublime is, for Kant, evoked by the sublime object, but not quite displayed in it, since infinity cannot be perceived. It is therefore an idea possessed by the observer, referenced by the sublime object. This invites another comparison with yūgen, which reveals not just the observed, but the observer; not just the limits of the seen but the limits of seeing. But here again this has to do not with the idea of the infinite as such, but the non-finite, precisely as what is beyond the finite. A long silence or shadowy landscape reveals by a feeling of mystery not just what is unseen, but what cannot be seen, what is never visible. Where the sublime with its reference to the power of the infinite stands in a close relation to terror, yūgen invokes rather the poignance of loss, and here is related to mono no aware or the ‘pathos of things:’ a feeling of sympathy for the endless passing of all that exists. The mysterious invisible beyond the perceived is not only the background of objects but that out of and into which all things, as well as the observer, emerge and return.

Sensitivity to yūgen is therefore not exactly taste. Although taste is likewise a cultivated aesthetic sensitivity, the capacity to experience yūgen is a matter of the whole personality, developed by not only the arts but by Zen practice. And the experience of yūgen is not only cultivated by Zen meditation, but itself points in the direction of satori (enlightenment). Indeed, it has been suggested that Dōgen's satori (expressed in for instance Genjōkōan, a chapter of the major Zen work the Shōbōgenzō) is precisely an epiphany of yūgen. Dōgen writes:

Seeing forms and hearing sounds with body and mind as one, [Buddhas] make them intimately their own and fully know them. But it is not like a reflection in a mirror, it is not like the moon on the water. When they realize one side, the other side is in darkness. When dharma does not fill your whole body and mind, you think it is already sufficient. When dharma fills your body and mind, you understand that something is missing. For example, when you sail out in a boat to the middle of an ocean where no land is in sight, and view the four directions, the ocean looks circular, and does not look any other way. But the ocean is neither round nor square; its features are infinite in variety. It is like a palace. It is like a jewel. It only looks circular as far as you can see at that time. All things are like this (Dogen 71).

Such an epiphany, of the limits of the perceiver with two sides (the visible outside and invisible inside), of finitude, or of the finite-in-the-infinite and the infinite-in-the-finite, is the experience of yūgen. The condition for this epiphany is the disciplined commitment to a transformation of the personality. And it is in this sense that Suzuki, as quoted above, can describe yūgen as disclosing the “secrets of reality.” But where Suzuki refers to these ‘secrets’ as the ‘eternal,’ he is speaking loosely for an English-speaking audience: this ‘eternal’ is at least not eternal being, or God, or otherwise an object for knowledge.

In 20th century Japanese literature, for instance in the works of Jun'ichirō Tanizaki (1886-1965), Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916), and Yukio Mishima (1924-1970), yūgen emerges as a feature of the Japanese as against the modern European lifeworld. Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows (1933) opens with a discussion of the author’s effort to build a house informed by traditional Japanese aesthetics, and the compromises with modern European construction (electric lighting, gas heating, tiled bathrooms, glass doors, and so on) that this involved. Here is for Tanizaki a point of contact between Japan’s ancient history and the demands and opportunities of modernization. The former is presented as a well-worn world of shadows, inefficient but elegant.

Tanizaki writes: “In making for ourselves a place to live, we first spread a parasol to throw a shadow on the earth, and in the pale light of the shadow we put together a house” (30). Life takes place in shadows, or within a play of light and shadow. A traditional Japanese house is designed not for complete illumination (with electric lighting), but for shifting patterns of light and shadow. Tanizaki continues: “The quality that we call beauty … must always grow from the realities of life, and our ancestors, forced to live in dark rooms, presently came to discover beauty in shadows, ultimately to guide shadows towards beauty’s ends” (31). For Tanizaki, the modernization of Japan meant the undoing of a world—not merely a world of politics or ethics, of matters of propriety or authority—but an aesthetic order: a world featuring yūgen, compromised by electric lighting, the aims of efficiency in production and governance, and industry otherwise. The traditional world, yūgen itself, can be preserved for Tanizaki only in literature.

In Grass Pillow (草枕 Kusamakura) (1906) Sōseki writes:

The woman’s figure was not fully revealed like the usual nude but could only be vaguely seen in an atmosphere of yūgen [darkness and mystery] that made everything within it appear ethereal. Her figure had a warmth, atmosphere, and rhythm that were artistically perfect, like a sumie [black ink] painting in which one can imagine all that has been suggested by the artist’s brush. (in Odin 248)

Sōseki like Tanizaki is concerned with the implications of Japan’s modernization. Again this means not just a loss of ‘tradition’ where this consists of principles or rules determining action, but of a cosmos featuring particular aesthetic tones and styles, experienced, expressed, and otherwise lived.

The protagonist of Sōseki’s novel is a Japanese poet and painter trained in the European style. The nude of the passage above is not the “usual nude” of European painting, where this is exhibits a laying-bare or disclosing of the human, of what is ‘human,’ as if something hidden within clothing and by a landscape–but a figure-in-context, always already both exposed and shrouded. As François Jullien argues in The Impossible Nude, the Greek/European or ‘Western’ idea of the nude displays a notion of the human defined by an essence revealed by dis-closure or uncovering. The Chinese did not conceive such a tradition of the nude, but displayed humans, perhaps the ‘essentially human,’ always in natural landscapes, with particular styles of dress, and among personal relations. The above passage suggests a similar distinction: the figure is not a revealed, ideal nude according to the European visual imagination, but a presence at the border or intersection of the revealed and the hidden. As ‘ethereal,’ therefore, this presence is a disclosure of the human as in its ‘essence’ mysterious, or shrouded, and as undefined. The human essence is eternal by virtue of its transience, in that it is defined by always passing away; and it is revealed by its obscurity, as never fully visible or defined.

Yūgen is as noted above a feature not only of experience but of the experiencer. It is further a quality of human action. Like iki it describes objects or images as well as personal style. Yūgen can mean something close to ‘grace,’ or ‘subtlety.’ As a visual scene may by a play of the concealed and revealed evoke a sense of mystery, so may human action that suggests rather than asserts, that is ‘evocative,’ or otherwise subtle. A person with such a style partakes of this quality of the cosmos itself, which is never laid bare except in the most narrowly framed ways. Yūgen, like other terms of Japanese aesthetics, cuts across distinctions between being, observing, and acting—a quality of all three. The feeling of yūgen both invites and is cultivated by a practice of yūgen as a matter of personal, religo-aesthetic living. And it is a quality of natural landscapes as well as art. Here as elsewhere Zen is the partner of the arts, and life is a project of art as artfulness is a matter of living.

Research and Discussion Questions

How may a ‘mood’ or aesthetic experience such as ‘yūgen’ be compared with an aesthetic judgment such as ‘beauty’? Consider the Kantian discourse of taste in relation to that of traditional Japanese aesthetic qualities: yūgen, iki, mono no aware, or wabi sabi, for instance.

What are the relations between religious practices and art (both artistic creation and aesthetic experience)? How might this relation vary historically and across traditions? What role may the question of the relation of art to religion have played in Japanese conversations about the process of modernization?

For a writer such as Tanizaki, why would yūgen have such special significance as a defining aesthetic quality of the Japanese tradition?

Consider the phenomenological language of figure/ground, perceptual ‘horizons,’ the ‘penumbra’ in the features of the prints in the collection. How might elements of composition such as the use of negative space and of light and shadow relate to these basic phenomenological notions of perception?

How might the phenomenological structures mentioned above find religious significance?

Discussion and Research Questions

Resources

philosophical resources

An article about Zen philosophy:

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/japanese-zen/

Introduction to Kant’s aesthetics: https://iep.utm.edu/kantaest/

A general introduction to Japanese aesthetics and the categories of art, as noted above:

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/japanese-aesthetics/

An introduction to ‘phenomenology’ as a method and a philosophical style.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/phenomenology/

references

Dogen, Eihei. Moon In a Dewdrop: Writings of Zen Master Dogen. Edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi. Translated by Robert Aitken, Reb Anderson, Ed Brown, Norman Fischer, Arnold Kotler, Daniel Leighton, Lew Richmond, et al. Reissue edition. New York: North Point Press, 1995.

Hisamatsu Sen’ichi, “Yugen,” in Itasaka, Gen, ed. Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan. First Edition. Tokyo ; New York, N.Y: Kodansha USA Inc, 1983.

Jullien, Francois. In Praise of Blandness: Proceeding from Chinese Thought and Aesthetics. Translated by Paula M. Varsano. New York: Zone Books, 2004.

Kant, Immanuel. Critique of the Power of Judgment. Translated by Paul Guyer and Eric Matthews. Revised ed. edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Odin, Steve. Artistic Detachment in Japan and the West: Psychic Distance in Comparative Aesthetics. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2001.

Soseki, Natsume. The Three Cornered World. Gateway Editions, 1988.

Tanizaki, Jun’ichiro. In Praise of Shadows. New Ed edition. London: Vintage Books, 2006.

Waley, A. The Nō Plays of Japan. New York: A. A. Knopf, 1922.

other sources:

Marra, Michael F., editor. A History of Modern Japanese Aesthetics. University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2001.

---. Modern Japanese Aesthetics: A Reader. University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1999.